Program Notes for September 24th, 2022

written by RSO Principal Cellist Michael Beert

Entr’acte by Caroline Shaw

Caroline Shaw

Composer: Born August 1, 1982, in Greenville, North Carolina

Work composed: 2011 for string quartet; arranged for string orchestra in 2014

First performance: string orchestra version – 2014, by A Far Cry Ensemble

Instrumentation: string orchestra

Estimated duration: 11 minutes

This is the first Rockford Symphony Orchestra performance of this work

Caroline Adelaide Shaw began her musical career at the age of two when she began to take violin lessons. She earned her Bachelor of Music degree from Rice University and her Master of Music degree from Yale University, both in violin performance. She began a PhD at Princeton University in 2010 and was the youngest winner of the prestigious Pulitzer Prize in Music in 2013 at the age of 30. She also received a Grammy for Best Contemporary Classical Composition in 2022. Her works have been performed by various ensembles and artists from the Baltimore Symphony to the Brentano String Quartet to Kanye West (sampled on The Life of Pablo).

The work featured in this performance, Entr’acte, suggests a work that opens a section of a play, opera/operetta, or musical. It aptly begins this concert. The work was inspired from a performance the composer heard of a Haydn string quartet performed by the Brentano String Quartet. In particular, the Minuet and Trio movement of his String Quartet in F Major, Op. 77 No. 2.

The contrasts between the Minuet and Trio sections were inspirational enough to the composer that she wrote the Entr’acte as an extension of the contrasts she heard in the Haydn. In her words: “I love the way some music suddenly takes you to the other side of Alice’s looking glass in a kind of absurd, subtle, technicolor transition.” She clearly takes contrasts and transitions as a focal point in this composition.

Georges Braque, Harbor. 1909

The work was originally scored for string quartet, and she scored this version for string orchestra at the request of the contemporary classical ensemble from Boston, A Far Cry. The work is roughly divided into three sections, similar to a Classical Minuet and Trio movement. It also uses a moderate triple meter associated with the Minuet. However, there are few similarities after that. Besides triple meter, the composer will use 7/8, 9/8, and even 11/8 meters to help create a fractured sound world. Silences in unusual places help keep this work feeling unsteady. Melodies are sometimes infrequent, and harmonies can range from tonal to non-existent. Things don’t go where you expect them. There is a sense of a cubist approach about the music and at the end, the orchestra goes off and leaves the solo cellist to end the work quietly in anticipation for what comes next in the program.

Tzigane by Maurice Ravel

Composer: born March 7, 1875, in Ciboure, France; died December 28, 1937, in Paris, France

Work composed: 1924 – for solo violin and piano; orchestrated by Ravel later that year

First performance: April 26, 1924, by Jelly d’Aranyi in London, England

Instrumentation: solo violin, two flutes (one doubling on piccolo), two oboes, two clarinets, two bassoons, two horns, one trumpet, timpani, percussion, celeste, harp, and strings

Estimated duration: 10 minutes

This is the first Rockford Symphony Orchestra performance of this work

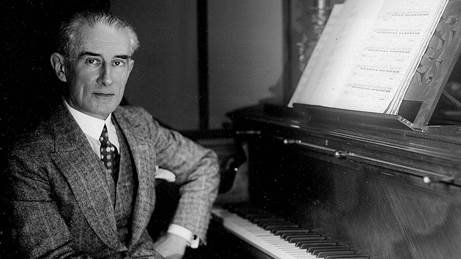

Maurice Ravel

The Tzigane by Maurice Ravel was written at a time when he was recognized as the chief French Impressionist composer of the day as Claude Debussy, the older champion of the movement, had died in 1918. The work comes at a time when Ravel was coming under the influence of modern classical experiments such as Arnold Schoenberg’s Serialism and Igor Stravinsky’s stripped-down Neoclassicism. Living in Paris, Ravel was also greatly influenced by American Jazz music. The work combines all of these styles: Jazz, Impressionism, modern classical movements, and Romani (formerly referred to as Gypsy) elements.

The title Tzigane suggests an influence by Romani music. Ravel is more influenced by the Romani idea of freedom of melody and form as well as Romani violin playing. The work does not quote actual Romani melodies but is more keeping in a style of musical freedom.

This performance’s soloist, Charles Yang, describes the work: “Ravel pushes the violin to its limits within this piece with its tender, singing lines to its raw and gritty textures. For most of the opening, it is almost entirely solo violin in an improvised fashion before the orchestra joins in. I’ve always loved how in this piece, the violin can sound like anything BUT a violin, at times sounding more like a voice or a strummed instrument.”

Czardas by Vittorio Monti Arr. Dugan/Yang

Vittorio Monti

Composer: born January 6, 1868, in Naples, Italy; died June 20, 1922, in Naples, Italy

Work composed: ca. 1904

First performance: unknown

Instrumentation: solo violin, two flutes, two oboes, two clarinets, two bassoons, two horns, two trumpets, percussion, and strings

Estimated duration: 4 minutes

This is the first Rockford Symphony Orchestra performance of this work

The composition here is a staple of the violin repertoire as well as of every Romani (formerly referred to as Gypsy) group. It has been arranged for just about every possible solo instrument imaginable and every possible accompaniment. There are versions for accordion, clarinet, saxophone, even string bass solo! This piece is a virtuoso violin solo meant to copy Hungarian melodies and idioms. It starts out slowly and winds up faster and faster as it goes along in its short time span. The music comes from an 18th-century military recruitment dance in Hungary. The idea was to recruit soldiers by first getting them to drink and slowly dance, gradually getting faster; then as the village men grew more drunk and wild, get them to sign up and enlist. Quite a strategy!

Our soloist, Charles Yang’s notes say: “This is one of those pieces that almost every violinist learns at one point in their musical lives. I remember learning this in my early years and it was just the most fun and show-offy piece I had ever played up until that point! I played it for EVERYONE because I wanted to show off my new shiny violin skills. Fast forward to today, I guess not much has changed. When Peter Dugan and I started playing concerts together, we would play this piece as an opener to our program. Every time we played it, we would improvise sections to a point where the piece became a completely original arrangement. This is our version of Vittorio Monti’s Czardas, orchestrated by Leonardo Dugan.”

House of The Rising Sun Traditional Arr. Yang

Composer: unknown – folk melody

Work composed: unknown – ca. 16th century England or France

Instrumentation: solo violin/voice, two flutes, two oboes, two clarinets, two bassoons, two horns, two trumpets, percussion, and strings.

Estimated duration: 3 minutes

The Animals

The song “House of the Rising Sun” has a great backstory if you are an ethnomusicologist, a 1950s American folk-song enthusiast, or an early Rock and Roll aficionado. Ethnomusicologists (folk music researchers) have traced the song to at least the 16th century in England as a song titled “The Unfortunate Rake.” Others have traced it possibly to France from the same time. It found its way over the Atlantic and was a song probably sung by the Anglo-Irish who settled in rural areas of southern Appalachia after North America was colonized.

It became popular in the 1940s and ‘50s in the emerging popular folk music scene by such groups as the Weavers and Woody Guthrie after it was “discovered” and recorded by the great American ethnomusicologist Alan Lomax. In the late ‘50s and early ‘60s it was covered by many artists, including Bob Dylan on his first record and by Pete Seeger. The Animals made it popular in the mid ‘60s. Its lyrics describe the hard life of people down-and-out due to hard living and possibly refers to a brothel, a juke joint, or any place where people can waste their time and their lives.

Our soloist’s notes are as follows: “Most famously recorded by The Animals, ‘House of the Rising Sun’ is a traditional folk song. Its origins are still not definitively identified but it has been covered and recorded by a wide range of artists including Woody Guthrie, Bob Dylan, and Nina Simone. I was first introduced to this song when learning guitar at age 15. My friend taught it to me after I had learned all of the open chords on a guitar and I was hooked on its “rising” chord progression and its story-like phrases. I of course had to find a way to play this on the violin. With my musical duo partner, pianist Peter Dugan, we made an arrangement for violin and piano. We wanted to capture the grit and raw essence of the song by infusing our classical and blues backgrounds. In this performance, you will hear the orchestrated version of this arrangement orchestrated by none other than Peter’s brother, Leonardo Dugan.”

Blackbird by Paul McCartney Arr. Yang

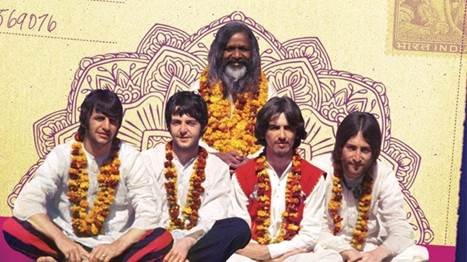

The Beatles, Paul McCartney (2nd from left)

Composer: born June 18, 1942, in Liverpool, England

Work composed: 1968

First Performance: release of the “White Album” on November 22, 1968

Instrumentation: solo violin/voice, two flutes, two oboes, two clarinets, two bassoons, four horns, and strings

Estimated duration: 3 minutes

The song “Blackbird” by Paul McCartney was written in 1968 when the Beatles were in India learning about Transcendental Meditation from Maharishi Mahesh Yogi. McCartney had early on given a couple of meanings to the song: that it was the song of a blackbird he had heard while in India; the song of a blackbird he heard while visiting a convalescing friend of his fathers; or his reactions to the Civil Rights troubles occurring in the United States at the time. The last answer is the one McCartney cites with more frequency than the other two in later interviews.

The opening guitar introduction and interludes are a result of he and George Harrison trying to learn a Bach Bourrée on classical guitar. He said it bothered both of them that they couldn’t quite get it down, but it obviously greatly inspired McCartney in the degree of intricate guitar playing he came up with for the song.

Mr. Yang’s comments about his arrangement of the piece: “I’ve always been intrigued by how simple this song can sound while being incredibly deep at the same time. Originally recorded as a solo number by Paul McCartney off of The Beatles’ “White Album,” I wanted to see how I could capture the same feeling and creatively spin this song together with orchestra. Using certain sounds and textures, the orchestra is turned into a rainforest of bird sounds. Lush lower strings start building harmony and tension until eventually the melody of McCartney’s voice is revealed using my violin. This arrangement was made in collaboration with Armand Ranjbaran.”

Symphony No. 8 in G Major, Op. 88 by Antonín Dvořák

Composer: born September 8, 1841, in Nelahozeves, Bohemia; died May 1, 1904, in Prague, Bohemia

Work composed: 1889 at Vysoká u Příbramě, Bohemia

First performance: February 2, 1890, with the composer conducting

Instrumentation: two flutes (one doubling on piccolo), two oboes (one doubling on English horn), two clarinets, two bassoons, four horns, two trumpets, three trombones, tuba, timpani, and strings

Estimated duration: 40 minutes

Most recent RSO performance: October 9, 2004, Steven Larsen conducting

Antonín Dvořák

The Symphony No. 8 by Dvořák is one that pretty much has it all: there are elements of Czech nationalism, Romantic influence from his mentor, Johannes Brahms, traditional symphonic elements from Beethoven and Schubert, and wonderful melodic writing so close to the heart of Dvořák.

Dvořák was a struggling artist until his 33rd year when he submitted several orchestral works and vocal selections to the Austrian State Prize for Composition. One of the judges was none other than Johannes Brahms, already a well-known composer in Vienna. It was Brahms who encouraged Dvořák throughout much of his career. Once, Brahms even wrote Dvořák to ask if he and his young family needed financial assistance during a tough time. Brahms gave Dvořák an introduction to Brahms’ own publisher, Simrock, so impressed was he by the Czech composer.

The Eighth Symphony was a step forward in the development of Dvořák’s writing. Composed in 1889, the work is less “Wagnerian” and stormy than his previous symphonies. It is much more pastoral and sunnier, being in the warm key of G major . The work is in the traditional four movement symphonic structure and its only deviation from standard form is the inclusion of a large Theme and Variations Finale. So, it is Germanic in its form, and Schubertian in its lyricism and harmony. However, its melodies are still linked to Bohemian/Czech folk-like music with occasional rhythmic twists and exotic scales—more Eastern European than German or Austrian. A mild use of Eastern European paprika spice in a traditional German stew!

The first movement begins with one of the most glorious cello melodies in the symphonic literature. Bird calls in the woodwinds answer followed by martial-sounding dotted rhythms. This movement is in a more traditional symphonic form with the material being fully developed. The recapitulation is found in the trumpets instead of the cellos giving the work a strong direction of movement and drama. The drama is relieved by the calmer bird-like music in the woodwinds. It drives to a loud conclusion with the full orchestra marked strongly with the timpani.

The second movement is not too slow and features wonderful writing for woodwinds and solo violin. There are dramatic elements that remind the listener of Beethoven, alternating with the wonderful lyricism of Schubert cum Dvořák.

The third movement is more of a Bohemian waltz in the minor key. Not quite as sophisticated as a Viennese waltz but more passionate in its drive and emotion. The Trio section features the solo oboe in the major key and displays more Slavic rhythms. Listen for the backup instruments to the oboes and you will hear three beats against two in different parts of the orchestra. Very subtle in its writing and its charm. The movement ends with a Coda that is no longer in triple meter but in two featuring the trumpets, almost as if it is foreshadowing the Finale in melody and rhythm. A perfect end to the third movement as well as a great transition!

The Finale, as stated previously, is the most dramatic of all the movements, starting with a formidable trumpet call that sets up a series of variations. After the trumpet introduction, the cellos and basses begin a series of variations built off of the trumpet theme. Each variation becomes more insistent and louder until the full orchestra takes up the joyful theme with French horns playing trills and strings playing chromatic scales around the theme. Then begins a set of variations in the minor that give the impression of a development much in the same manner as Brahms had done in the Finale of his Fourth Symphony four years previously.

The movement begins to reach a climax where there is then a recapitulation of the opening theme and variations in the cello and bass. It follows much of the same material as early in the movement. This leads to a Coda of wonderful nostalgia and tenderness, particularly in the solo flute. Just as the movement dies away in what should be burnished twilight, the listener is jolted awake by a loud Presto section that restates the opening trumpet theme. The orchestra then races to the finish in a loud fortissimo ending that is nothing short of brilliant!